With trillions of dollars in new work coming online this year, contractors — already struggling to retain craft workers during a historic shortage — now face the challenge of competing with big projects that come to town with a lot to offer workers.

This year, the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, which allocates $39 billion to build and expand semiconductor manufacturing plants, will create thousands of new construction jobs — on top of what Ken Simonson, chief economist for Associated General Contractors of America, called “an unusually large concentration of really large projects right now.”

“A remarkable number of multibillion-dollar projects are showing up in many states,” Simonson said. “In many cases, the owners of these projects, while not insensitive to cost, may have more flexibility and willingness to pay and offer a range of benefits that smaller companies can’t.”

When projects compete for the top available labor, “it gets messy,” said Portland, Oregon-based Eric Grasberger, construction and design group chair of national law firm Stoel Rives.

“In order to compete, the contractors on those jobs have to go to the owners and say, ‘We can’t get the labor, and we’re not going to get the labor unless you authorize an increase in the hourly wages, the per diem or both — or perhaps other incentives,’” Grasberger said.

To attract and retain workers, many local companies are finding more compelling benefits well beyond money. They’re offering everything from hot meals and heated bathrooms on jobsites to paid volunteer and educational opportunities that may even extend to workers’ families.

“They’ve got to sell something bigger than just a project, because typically those industrial projects pay a lot more per hour than your average contractor might pay,” said Greg Sizemore, vice president of workforce development, safety, health and environmental for Associated Builders and Contractors. “In middle-class America, it’s about selling the value, which is beyond just the dollar.”

Free lunch, wellness centers

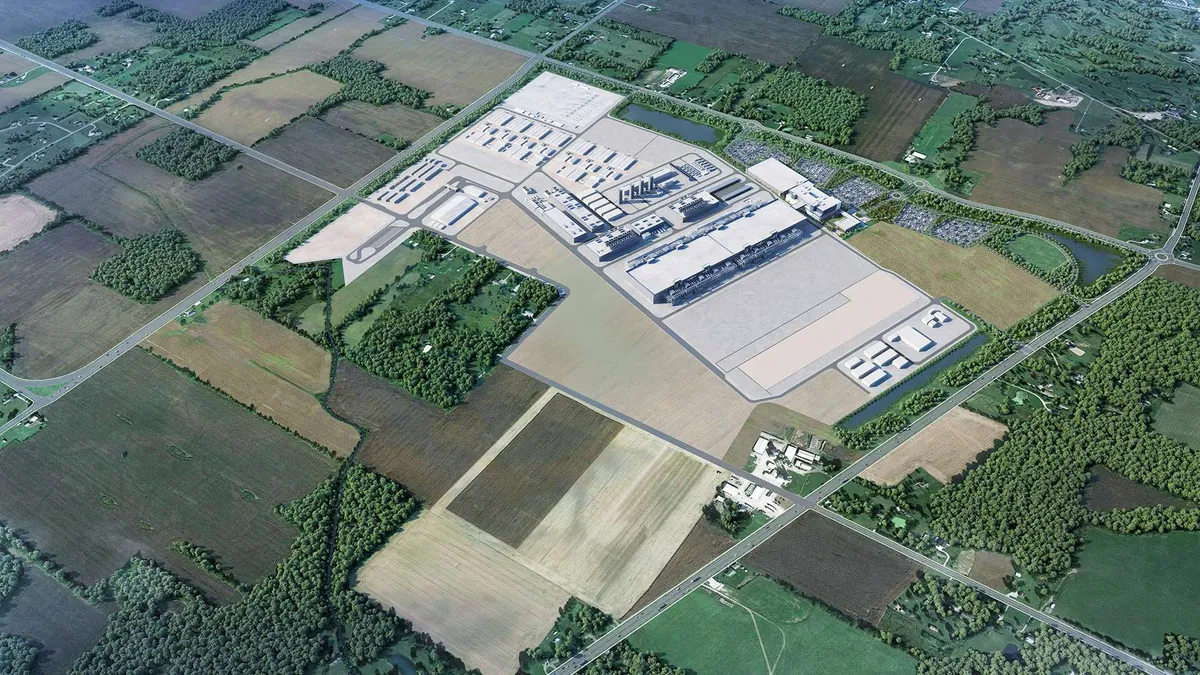

In central Ohio, megaprojects are becoming the norm rather than the exception — a $20 billion semiconductor manufacturing plant for Intel, a $4.4 billion electric vehicle battery plant for Honda, data centers for Google and Amazon, and a biomanufacturing plant for Amgen are just a few.

The flurry of building activity means construction workers have the potential to make as much as $135,000 per year, said Dorsey Hager, executive secretary-treasurer of the Columbus/Central Ohio Building & Construction Trades Council.

Throwing more money at workers to keep up with megaproject salaries is not an option for many local contractors, but Dorsey said it’s probably not the most effective tactic anyway. In their efforts to hang onto workers, central Ohio construction firms are offering amenities such as free breakfast and lunch, onsite wellness centers, heated restrooms and changing areas and convenient paved parking, he said.

Sizemore said tradesworkers used to ask just three questions when considering a job: how much it paid per hour, how many hours they would work and what the per diem was.

“Now, the whole world’s changed,” he said. “We’ve got new people coming into the industry who are looking for opportunities to go to work for contractors that have a long-term value proposition that meets their needs — things like paid time off, maternity and paternity leave.”

Younger generations of workers are asking more questions about company culture, what types of projects they would be working on and even safety protocols, said Keyan Zandy, CEO of Skiles Group, a mid-size general contractor in Dallas.

In his market, Zandy is facing competition from a host of massive industrial, infrastructure and residential projects such as a $3 billion 112-acre mixed-use development that recently broke ground near Dallas. The Mix — which will include 375,000 square feet of retail, a 200-room boutique hotel and a 400-room business hotel — will be under construction through 2026.

Skiles Group makes a concerted effort to align workers with the firm’s core values and include them in all of the company’s activities, whether volunteer programs or company picnics, Zandy said.

“It’s about not treating your labor like they’re a secondary component of what you do,” he said. “That’s really the main thing—we should be doing everything we can to empower these people because if it weren’t for them, nothing would ever get built.”

While smaller firms might not be able to compete when it comes to salaries, they have the advantage of being able to offer workers more personal relationships with owners and senior management and possibly even meaningful ownership shares, Sizemore said.

“It really is about making people feel like they’re a part of something as opposed to just working for Amazon,” he added.